I know this sounds quite scientific;

but it’s not. In fact, I do assure you that what follows in the

space of the next two pages – or thereabouts – is the intentionally

fragmented thought, in order for it to look like it has always been

part of a unitary text, of a man who, in doing so, has risen himself

high above time, to look into it, and high above all temporal

demarcations, to look at them.

What follows below is, then, this

man’s line of thought in the form of more than one line being enough

to comprise this very line. So, all the necessary lines that his

line of thought covers will have to be dialogue-like because this is

the only way all the inner lines of his line of thought can

communicate with each other to form his singularly positive line of

thought on his a-temporal account of time.

This man thus stands against, and in

front of, this man, his himself, for the following inquiry into

time’s lack of temporality in a world that shouldn’t miss it at all.

“My dear temporarily alienated self,

let’s then embark on our dialogic expedition by simultaneously

beginning and ending time and its temporal course through the

world.”

“Notwithstanding my acceptance of

your proposition, I must ask you why you think we should have this

talk at all about time and its becoming a-temporal by means of a

simultaneous entry into, and exit out of, time itself?”

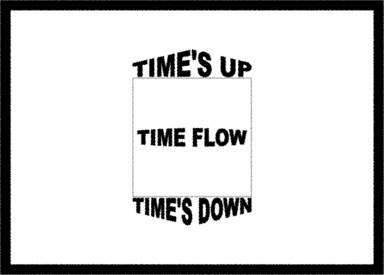

“For it’s precisely in this

simultaneity of time’s points of existence (the beginning being its

point of existence through which it comes into existence and the end

being its point of existence through which it goes out of

existence), which might also be referred to as the mutual

annihilation of its points of existence, that time can truly be

a-temporal. If you deprive it of this simultaneity, or annihilation,

time will then always be fated to bear its own temporality with

dignity and, consequently, fatally bear on its very temporality.”

“I understand now. So, time has to

begin and end its temporal course, as it were, at the same time in

order for it to become a-temporal. Oh, I think I get you now even

more than when I used to: if it annihilates both its beginning and

its end, time can then be a-temporal because it no longer has any

point of existence either to come into existence or to go out of

existence; so, by actually ceasing to exist, it becomes a-temporal.”

“Very correct: time can only be

a-temporal if it completely ceases to exist. Out of its existence,

or, as some might argue, beyond its existence, time is superiorly

a-temporal.”

“I understand… but this in itself

and by itself raises two difficult problems to overcome, and I’m

afraid that what you have just said, your solution to time’s need to

be a-temporal, which is equally mine, as I’m your yourself, will get

complicated exponentially by its under-running, and intellectually

stalking, aporias. One is, if time becomes a-temporal

only upon its going out of existence, since it then no longer exist,

how can it still be one way or the other, temporal or a-temporal? By

ceasing to exist in order for it to exist in just one specified way,

doesn’t it cease to exist at all, including in the way in which it

has been prescribed to exist if it ceases to exist? Of course, this

would necessarily imply that, in order for time to exist – in one

way or the other – it doesn’t have to cease to exist at all, but

only partially. Time, if it wants to become truly a-temporal, it

does need to cease to exist, by annihilating both its beginning and

its end into a simultaneous taking out of existence of both its

beginning and its end, but it merely has to cease to exist

partially, and not completely, when it would actually no longer be

able to be either temporal or a-temporal simply because these two

modes of existence have become invalid owing to its going (or having

recently gone) out of existence. Time thus needs only a partial

going out of existence in order to cease to exist thoroughly if it

truly wants to become a-temporal. And two, logically out of

one, is, if time only needs a partial going out of existence

in order to cease to exist completely so that it may acquire a real

a-temporal nature, does this mean there can generally be two ways of

going out of existence: a partial one, which ultimately takes

nothing out of existence if it still exists to be one way or the

other, and a total one, which would positively take out of existence

everything that has so far existed, letting thus nothing of prior

existence still to exist to be one way or the other? So, you see, my

good self of mine, these are the two difficulties that might stop

you, while you’re still not me, from making time genuinely

a-temporal for all eternity or, at least, for the duration of this

brief account of time’s lack of temporality. How do you respond to

these two aporias and what is your solution to circumventing

their illogical grip?”

“My good self, thank you for your

not being myself yet. If you had already been myself, I would never

have taken notice of these two hurdles in the way of my attempt at

making time truly a-temporal. And, of course, thank you for showing

them to me in as bright a light as only the light of prolix

arguments can offer. If, in what I have to say next, in conclusion

to your having found many a fault with my attempt at making time

a-temporal, and until the conclusion of our debate on time’s lack of

temporality, you look for two counter-aporias, which, in

their turn, would ad infinitum propagate other rows of

aporias, I must then inform you this is not my current line of

thought, and it will not be mine as long as we are still disjointed

into my independently self of yours and, respectively, your equally

independent self of mine. My line of thought doesn’t lie in

countering one already revealed set of aporias with another

one just about to be revealed. Instead, I will go on pursuing my

attempt at making time duly a-temporal and giving it a proper

account of how it has become so, irrespective of how many other

aporias I’ll still be running into.”

“You have all my attention and my

net of logic is extensively cast to catch any other illogical glitch

that might rise from your positively free line of thought.”

“So, I have originally stated that

time can be made a-temporal if its beginning and its end are

simultaneously suppressed. I have also said that it’s only in this

simultaneity (or simultaneous annihilation of both its beginning and

its end) that time gets what it needs to become truly a-temporal.

But, in stating all this, which you have plainly disagreed with by

affirming the logical impossibility of time’s becoming really

a-temporal on the grounds of its not being able to cease to exist

partially in order for it not to cease to exist completely,

have I also said why time has to do away with both its beginning and

its end if it wants to become purely a-temporal?”

“You seem to have only given an

insight into how time becomes a-temporal: by taking out of

existence its beginning and its end, and by depriving itself of its

temporal birth and death.”

“Indeed, I have so far been quite

scanty in providing a good explanation of time’s reason for wanting

to become a-temporal; but I seem to have been even scantier in

giving the true mechanics of time’s becoming a-temporal. I think it

doesn’t really matter why time wants to become a-temporal; we all

know, while we’re still different from each other, that time only

wants something as long as we want time to want something. So, to be

honest, it’s us who wish time would be this way or the other way: in

my case, while it’s still mine, a-temporal. As for how it’s become

so, or can indeed become so, based on my solution to this problem, I

needn’t talk much. The mechanics of time’s lack of temporality is

quite simple. They follow a pattern very much in line with this

temporal insufficiency that makes time truly a-temporal: a different

dearth, which is not temporal, but rather of proportion. Time seems

to become a-temporal only if parts of it – its extremities – are cut

off of its body. Apparently, the time that is a-temporal is a

mutilated time. A time that is incomplete: a time that is missing

something from its body. Then, if this is the case, I can ask

myself, feeling now en route to rejoin you, my former, primal

and basic self, how can time be both incomplete and mutilated (that

is, a-temporal, at least according to my definition), and also whole

(that is, of time; it being, a-temporal or not, of an evenly

distributed substance)? Seemingly, only out of, and beyond

time, if it’s to become truly a-temporal. This means that time, when

it’s a-temporal, or in its a-temporal habiliments, is either

incomplete and mutilated, hence handicapped and not able to run and

pass, or whole and fully able to run and pass, but rather than being

in, and belonging to, this time, which borders on its past (a

beginning that always ends) and its future (an end that always

begins), it is actually out of, or even beyond it. In

conclusion, it having finally arrived at the last line of my line of

thought, now almost indiscernibly yours, time can only be a-temporal

if it does go out of existence; however, this is neither partial,

nor total, for this going out of existence doesn’t mean

extinction, but rather mutation; so, time can only become

a-temporal if, by going out of existence, and instead of ceasing

ultimately to exist either partially or completely, it mutates

itself out of its temporal existence, which is limited by a

beginning and an end to time itself, straight beyond its temporal

confines, in the purest lack of temporality I will ever wish to

know.”

|