|

Geometry and "Point of View"

by Adi Da Samraj

|

Cézanne once stated something to the effect that the

making of the structure of an image can be understood in

terms of cylinders, cones, and spheres. All those are

curved, three-dimensional forms. So Cézanne thought in

three-dimensional and curvilinear terms.

|

|

| |

Adi Da Samraj |

|

While

this statement is not entirely representative of how Cézanne made

images, much has been made of that statement by modernists, who

have often made images based on geometric concepts of some kind or

another. But it is a plastic concept, a continuation of the

academic tradition, even of the traditional understanding of how

to build up a picture. It is not an understanding of reality

itself.

Cézanne only made this remark one time, and he did not

mean he was literally making images that are made of

cylinders, cones, and spheres. It was just a reference he

made in a letter to somebody about how to build up a basic

structural form tacitly—not actually making a picture of

cones, spheres, and cylinders—and then fill it in. It was

not anything like that, but (rather) merely a general

sense of structure. That was part of the academic

tradition.

My

own artistic work with squares, circles, and triangles—or linear,

curvilinear, and angular—is another matter. My artistic work is

about the structure of conditionally manifested reality, the

structure of perception, the structure of brain-controlled

awareness or perception. My artistic work also relates to the

fundamental structure of conditionally manifested reality in the

human scale—gross, subtle, and causal—with the linear (or square)

being associated with the gross, the curvilinear (or circle) with

the subtle, and the angular (or triangle) with the causal. It is a

different understanding altogether, although it does recall

something of the remark Cézanne made, which modernists have made

much of.

When

I was a boy, I used to watch Jon Gnagy, who was an art teacher on

television at the time, and I got this kit that you could order.

Jon Gnagy would draw an image—for example, a house in the woods by

a stream—and make it out of fundamental shapes, then shade or

round them, and so forth. In other words, he was building up a

picture using geometry. He was continuing this tradition, this

notion—something of the modernist tradition altogether. Thus, I

was getting artistic training in the tradition of modernism, and

in the mode of Cézanne particularly—without the names being

mentioned, without saying anything about modernism. It was just

art-school picture-making—while, in fact, this approach was based

on the modernist tradition and Cézanne’s remark, although Cézanne

himself did not actually make paintings using these forms. He was

just talking about a way of understanding (from an academic

perspective) something about how to generate a sense of how you

build up a picture or an image.

Unlike the impressionists, Cézanne was not interested in merely

responding to what colors were coming to the eye. He was

interested in thinking structure and making structure—of color,

rather than of lines—seeing the surface not as a flat continuity,

but still based on the three-dimensional “point of view”. There

are many different “points of view” reflected in Cézanne’s images.

Each day, he would change his position—standing over here, looking

at a bowl from above, or straight on, or whatever. He painted it

as it looked that day, because that was his perception. He wanted

to see what he was seeing. Working from different “points of view”

was not so much because he had a modernist understanding of the

attempt to transcend perspective. Cézanne was a realist. It is

just that he moved around. Sometimes his fruits would get

overripe, so he would be working on painting a pot, after the

fruit in it had rotted, and be doing the pot from a different

place. He had to really be seeing it as it was in front of him at

the moment. That was the reason why he changed his “point of

view”, while a modernist would work intentionally on changing the

“point of view” of different aspects of the image.

My

own artistic work is about transcending the position of egoity (or

“point of view”) altogether. While something of the dialogue of

modernism in Cézanne is associated with the image-work I do, those

who are considering this seriously should see and understand the

profundity of the difference, also. They should understand the

particularity of this summation of what I am doing. What I am

saying is this: It is not “point of view”, not “point” in space

and time, but reality itself that is the basis for the images I am

making, the entire process of image-making that I am developing.

It is not “point of view”—as if, for instance, to make a circle,

you would point a compass point down and then rotate the pencil or

the inscribing material to make a circle from that point, or that

you would have to measure the circumference around a point by

multiples of pi, which is an irrational number. If the natural

world was based on measuring circles using pi as the measure, the

natural world would never have happened! It would not be happening

now, because pi is not a precisely determinable number.

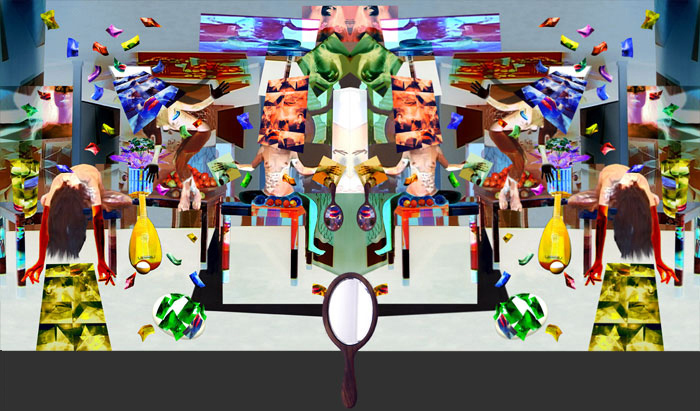

Adi

Da Samraj - Spectra One

In

that case, how is everything happening? Conditionally manifested

reality is self-organized spherically—not from the “point” that

views it, but from the totality of the happening. That is the

“position” of the imagery that I am making. That is the “position”

of the process of making imagery in which I am involved.

Therefore, I call it “non-subjective” image-art. It is not

“point-of-view” art. It is not merely multiple-“point-of-view”

art—whatever the appearance may be, or whatever it may suggest

relative to ordinary perception. There is some suggestion of that

kind, of course—but it is egoless, not “point-of-view” art.

However, in the image-art I make, I do comment on “point of view”.

I reflect it, and demonstrate the force of reality relative to

what is otherwise “point-of-view” perception. There are many

elements of meaning and many visual characteristics in the images

I make, but it is not based on generating circles or spheres from

“point of view”. It is based on how reality is self-organized

spherically—prior to “point of view”, prior to a center or a

“point” from which to view it or generate it.

The

illusion of egoity is that, somehow, the world is being generated

from your own position, or being shown to your position. That

suggests the idea that the human being must make the measure of

reality and control it—whereas reality is actually self-generated,

beyond “point of view”, beyond control, prior to “point of view”,

prior to control, prior to separateness. You could say the work I

am doing is “Reality-Art”, or (as I call it) “Transcendental

Realism”—not the realism of conventional perception, such as

Cézanne, for instance, was considering.

The

art I make is not about building up pictures based on geometries

manipulated from a “point of view”. Rather, it is about the force

of reality itself, and generating images based on that

force—which, most fundamentally, is a spherical force. It is a

force of prior unity (or all-inclusiveness). Thus, when I make

images on a flat plane, the fundamental impulse is not to imitate

three-dimensionality. It is about a flat rendering (or

demonstrating) of the nature of the force of reality itself—prior

to “point of view”, prior to egoity. I am not just involved in an

aesthetic or a program for how to make a picture from shapes and

so on. I am not sitting in “point of view”.

Therefore, through artistic means (as I also do through verbal

means), I am working to demonstrate the nature of reality

itself—just as it is, as it is self-evident to me already. I am

not merely trying to make paradoxical images, but rather to

demonstrate how the world is in reality itself, and how awareness

of the world as it is in reality itself can show itself even to

humanity in general, human beings who are otherwise seeing things

from “point of view”, and who are also habituated to looking at

pictures that are built upon conventions historically agreed upon,

such as the Renaissance idea of perspective. The imitating of the

real world through the use of rules of perspective started in the

fifteenth century, and then that became the academic convention of

how to make pictures.

Adi

Da Samraj - Spectra Three

One

of the aspects of modernism that changed that was the

relinquishment of the idea of perspective—as in Cézanne’s case, or

the work of cubists such as Picasso and Braque, who began making

pictures based on multiple “points of view”. But, even so, that is

still taking the position of “point of view”, to make a picture

that is paradoxically associated with the “point of view”. That is

not what I am doing.

This

is, in part, why I am tending toward the flat two-dimensional

approach now. I am not trying to imitate three-dimensional

reality. In Cézanne’s statement, he is still talking about

three-dimensional forms—cylinders, cones, and spheres. He is not

talking about circles, triangles, and squares—not flat geometries.

Rather, he is still conceiving things conceptually and

understanding them in terms of volume—still seeing forms in the

plane of conventional realism, in the mode of traditional

picture-making based on “point of view” and perspective.

I am

not really involved in picture-making. The position in which I am

making images is not simply picture-making in and of itself.

Rather, the basis on which I am making pictures at all is the same

in which I speak and live and work altogether. It is already prior

to “point of view”, already without “point of view”.

“Point-of-view” perception is part of the convention of day-to-day

awareness. On the other hand, neither am I simply trying to make

pictures that are paradoxical over against “point of view”—rather,

I make images that are prior to “point of view”.

Therefore, the images I make are not merely images based on

multiple “points of view” and the deconstruction of perspective.

Rather, they are generated prior to “point of view”, prior to

conventions of picture-making based on the tradition of

perspective and rules in the academic tradition. I go beyond all

those conventions.

Just

as using the camera (which is a “point-of-view” machine)

inevitably makes images on a certain basis, I have had to work

with the camera now for years to overcome “point of view”. Of

course, I used multiple exposure as a means to do that. And that

was something I was particularly doing when I was using film

cameras. Now that I am using digital cameras, I am not trying to

make multiples—although I could.

In

fact, at the moment, I am not using photography at all, as I was

before. When I shoot images, I shoot single-frame forms. I have

not been including them in the images lately (although I expect to

do so again)—but, day to day, I respond to them. They are sort of

like a sketchpad. I bring them to the studio, work further by

responding to them, and generate images in response to them,

rather than actually putting the photographs into the image. I

expect to use the photographs within the images in various ways,

but still as a means of going beyond this “point-of-view” machine.

The

body is a “point-of-view” machine. It is an ego-machine. I do not

want to simply use it as such, as a convention of communication or

perception, but (rather) to go beyond that. The body can be a

means for generating images for others, who are also bodily

existing, to see—and, optimally, for those seeing the images to go

beyond just looking at them and to actually participate in them.

I am

manifesting the self-organizing force of reality in the context of

perception and communication—and, therefore, of images.

Cézanne and the impressionists characteristically used little,

short brushstrokes. My so-called “brushstrokes” are very, very

small. They are bytes, pixels—more directed to how the brain

organizes and generates visual perception. My interest in the

digital process, however, is not merely technical. In fact, I do

not really want much to do with that. I want to simply make use of

the visual characteristics (as with the camera) that are possible

using the digital means without getting involved in the machinery

of it, the procedures of it, the linearity of it, and all the rest

of the mind of it. I just work on it strictly as a visual process,

without having to become embedded in the “technology-position”. I

prefer to keep apart from that, just as I do not want to get

over-immersed in the technology of the camera or anything else

like that. I am always going beyond it, always standing prior to

it, standing free of being subordinated by it.

So

when I work, I am always standing outside the “seat” of the

technology. The interest is strictly in terms of visual or

perceptual phenomena, so that I am still working with the

fundamentals of image-process, or the fundamentals of perception,

rather than getting involved in “techie” business (either with

camera or with digital means). In that case, I can be fully

involved in the perceptual process and in the generating of images

that manifest the characteristic of reality itself.

Copyright © 2007 ASA. All rights reserved. Perpetual copyright

claimed.

|