|

Michael

Madore, who has Asperger's Syndrome (a form of autism),

started to draw maps and diagrams as a child in order to

corroborate increasingly specialized interests that began with

geography and culminated by the age of twelve with an obsession

with office market vacancy rates.

As a teen he took refuge in cartoons, radio

playlists, mechanical drawing, and weather statistics. In college

he majored in art history, focusing on medieval manuscript

illumination and nineteenth century artists/illustrators such as

William Dadd, Victor Hugo, and Grandville.

After graduating in 1977, Madore moved to New

York where he first began to consciously make "art" while

remaining on the periphery of the emerging East Village art scene.

He moved to New Haven in 1983 and for nearly a decade he continued

to work in relative isolation, teaching himself to paint while

meticulously creating and cataloging a world populated by the

likes of King Charles (who had the ability to render himself

invisible or to take on animal forms), the Sirenians (a quasi

scientific/monastic tribe of nervous, absentminded "researchers

and sensors"), and innumerable forest, aquatic, and space

entities. In 1987, while hospitalized at Yale-New Haven Hospital,

he took the advice of his psychiatrist and entered the Yale MFA

painting program. After graduating in 1990, Madore moved back to

New York where he has continued painting and drawing while working

as a medical editor, proofreader, and writer on topics ranging

from synesthesia, tics, and ikebana.

|

|

|

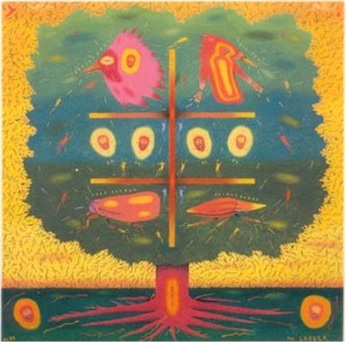

"The

Ladder" (oil on canvas 42" x 42") |

I have an autistic disorder,

and I tend to be very literal. So when my psychiatrist at Yale-New

Haven Hospital suggested I apply to the Yale University School of

Art, my response was “Okay.” I thought he was talking about a day

treatment program!

I have to admit, when I got accepted I

didn't really think it was a big deal until I saw how seriously

the other students were taking the whole thing. I mainly saw it as

an opportunity to do research in cartography, which is a subject

I've been strongly interested in since I was a kid. Cartography

and drawing were my way of coping. By 6, I had memorized all of

the islands off the coast of British Columbia, and by the time I

was 11 or 12, I was “designing” shopping centers, figuring out the

best arrangement of all the retail components. Then when I was a

teenager, and even now as an adult, I became obsessed with

commercial leasing activity. I have to know office vacancy rates.

And not merely in New York City where I live, but nationwide. To

this day, I also remain obsessed with blueprints and any kind of

technical drawing, since they neutralize the threat posed by full

dimensionality. I got a full scholarship to go to Trinity College

[in Hartford, Conn.], where I started off majoring in

architecture, and ended up in art history, and then in English

because I had some time to kill and thought psychoanalytical

literary theory would magically explain social behavior. I had

always been very anxious about hidden agendas and reading between

the lines. I graduated with a dual degree in art history and

English. I was going to go and get my master's in English, but I

knew, without knowing the name of it, that I was incapable of

this. I couldn't write more extended and logically consistent

academic types of papers, so I had to abandon a university career.

I didn't even know how to shake hands until after college.

|

|

|

|

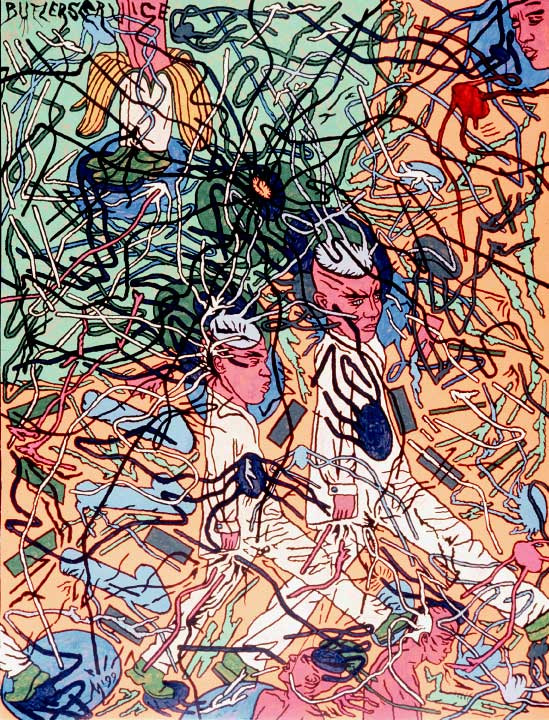

"Eye

raffle" (ink & acrilyc on paper, 25 x 10", 2000) |

"Dolores" (mixed media on paper, 19x25", 2001) |

Cartography and drawing

are my way of coping with Asperger's Syndrome. As a kid, I was

diagnosed with everything else but that. My AS is comorbid with

Tourette's and ADHD. I use art to try to figure out how to

communicate in ways that other people seem to take for granted.

One of my recent drawings, “Eye Raffle,” was done specifically to

help me clarify the problem of the logistics of eye contact. This

was very hard to do, because I've always felt eye contact is so

arbitrary—when you look at someone and how long you look at

someone and how you return a gaze. It seems like a raffle.

|

|

The pieces that were on display

at the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore were newer and

reflected my obsession with opiates. Mercifully, I was not a good

addict. All I take now is Adderall. I used to take anxiolytics,

but my doctors stopped that because of the potential for working

me back into opiates. When it comes to medication, I usually have

the opposite reaction to what's expected. Pot was like an

amphetamine. Cocaine makes me sleepy. Some anxiolytics would

actually make me “hyper.” I used heroin because it would shut down

the sensory overload. Anxiety is still my biggest issue. I spend a

lot of time trying to tone down a lot of conflicting sensory

information. I am acutely aware of noise.

I am perpetually trying to figure

out, “Am I hearing something? Am I overhearing the sounds of

my cats? Am I over interpreting?” Heroin quieted this internal

interrogation, and it helped me retain a certain

functionality. For me, Adderall works as an antidepressant in

addition to calming and focusing me in terms of executive

function. Drawing forces me to coordinate my senses, and it

helps me cope with my illness. It allows me to “remap” myself,

in a sense. |

|

"

Butler service" (ink on paper, 25 x 19", 1999) |

I've always been obsessed

with diagrams. I have a problem with volume and dimensionality,

the sense of moving through space, which manifests itself in a

kind of motor clumsiness and an obsession with symmetry. I

constantly feel compelled to center or “arrange” myself in

whatever space I'm in. To help overcome this I joined a gym, which

helped. I started going to dance performances, but then I started

becoming obsessed with the history of dance. I even considered

becoming a dance critic, but I knew there was no way I could

verbalize physical movement except in a disjointed, rambling

manner. Plus, I'd never match faces with names, and [would]

thereby incur the wrath of equally high-strung, creative types. I

was just part of a big autism study, and for part of it they test

reflexes, and [the researchers] would say “pull,” and I didn't

know how to translate that into the proper body movement. I kept

doing the opposite, and [the researcher] kept getting really

frustrated. I was trying, but I didn't understand how you'd pull

your leg out. It's the same with choreography. I don't understand

how a person can translate a verbal command into physical action.

Autism is like continually mistranslating or getting stuck on a

missing link or conjunction.

|

|

|

|

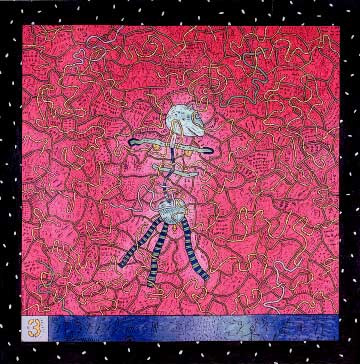

"Trapped"

(enamel/magic marker on paper, 1979) |

Curiously, the one group

who has been the least supportive of my diagnosis is my artist

friends. I think they feel the most threatened. And I agree to

some extent, because it seems that the very concept of creativity

is becoming medicalized. I agree with Lawrence Osborne and his

book, “American Normal: The Hidden World of Asperger Syndrome.” He

worries that we are medicalizing creativity to the point where it

becomes a diagnostic cluster of symptoms. Years ago, it was

theorized that perhaps the creative process itself is linked to a

kind of bipolar disorder. And I think when people now hear autism,

it really freaks them out, because now Virginia Woolf has turned

into Rain Man—and I'm assuming it's not a pretty picture.

I don't see my condition

as a stigma at all. Ever since I was little, I was used to being

way out on the periphery in order to attain safe and critical

distance. I was very good with language, so I was able to bluff

myself out of many potentially bad situations by sweet-talking

potential adversaries into oblivion. By the time I got to college,

it was okay to be in your own world; everyone was specializing in

the '70s. I don't really feel threatened or compromised by people

pathologizing me, or turning me into a case study, or trying to

force a causality, or a 1:1 correspondence between my work and my

autism.

|

|

|

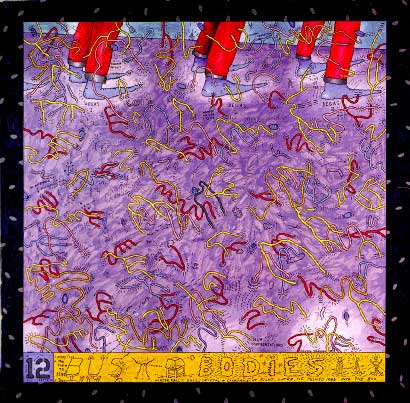

"Busy

bodies" (enamel/ magic marker on paper, 1979) |

|